What’s inside a computer?

In this series of three articles, I will explain what each of the CPU (Processor), RAM (Memory) and Storage do in your system. I’ll keep it simple but useful so that you have a solid understanding when it comes to making an informed choice about your next computer.

What does the CPU do?

Your computer (or phone, or tablet, or games console…) works in quite a fundamentally simple way. You ask it to do something. The instruction gets passed to the CPU, which completes all the calculations necessary to successfully carry out that instruction, before showing you the result of that instruction on the screen. The CPU, or Central Processing Unit (or sometimes just Processor) is often talked about as the brain of your system. A fast CPU will complete tasks more quickly, giving you a faster computing experience.

How do I recognise a good CPU?

As you probably know, if you ask me for my recommendations for a computer and tell me what you’re going to be using it for, I’ll make three recommendations for you. This article explains in a bit more detail about the process of recognising what CPU will do the job and, more importantly, how to avoid ones that won’t.

It can be a bit daunting when there are so many ways in which CPUs can differ, but I’m going to start with what I think is the most important piece of information to know: There is a lot of marketing speak when it comes to CPUs. That is, manufacturers often emphasise specific numbers or certain keywords to make a CPU seem better than it is.

In more detail: History of consumer CPUs

In the old days, the key statistic was simply how fast your CPU was, sometimes referred to as the clock speed. This was measured in hertz (Hz – cycles per second), then KHz (thousands of cycles per second), MHz (millions of cycles per second) and finally GHz (gigahertz – billions of cycles per second). By just making processors work faster, everybody could easily tell which CPU was the best. This made choosing a CPU relatively simple.

Then around 2005, the big CPU manufacturers released new processors that had dual cores. That meant that instead of just one brain, these CPUs had two. The problem up to that point had been that just making CPUs work faster also made them heat up considerably. By introducing dual core CPUs, they were able to increase performance by up to 80% while still using similar levels of power and keeping heat down. But this presented a marketing problem. Who was going to buy a 2.8 GHz Pentium D in 2005 when they could have bought a 3.8 GHz Pentium 4 just a year before?

So began the tradition of slapping new brand names onto CPUs and promoting the brand name rather than a specific number. This had the benefit of helping people to recognise that there was more to how well a CPU performed than just clock speed. However, it opened the door to a world where it became difficult to understand exactly what you were getting. We had Pentium D, then Core 2 Duo, then Pentium Dual-Core, then Celerons and Xeons. And this was all just from one chip manufacturer, Intel. AMD – the other big CPU manufacturer in computing at the time – had its own way of naming things.

Simplification – a necessary step

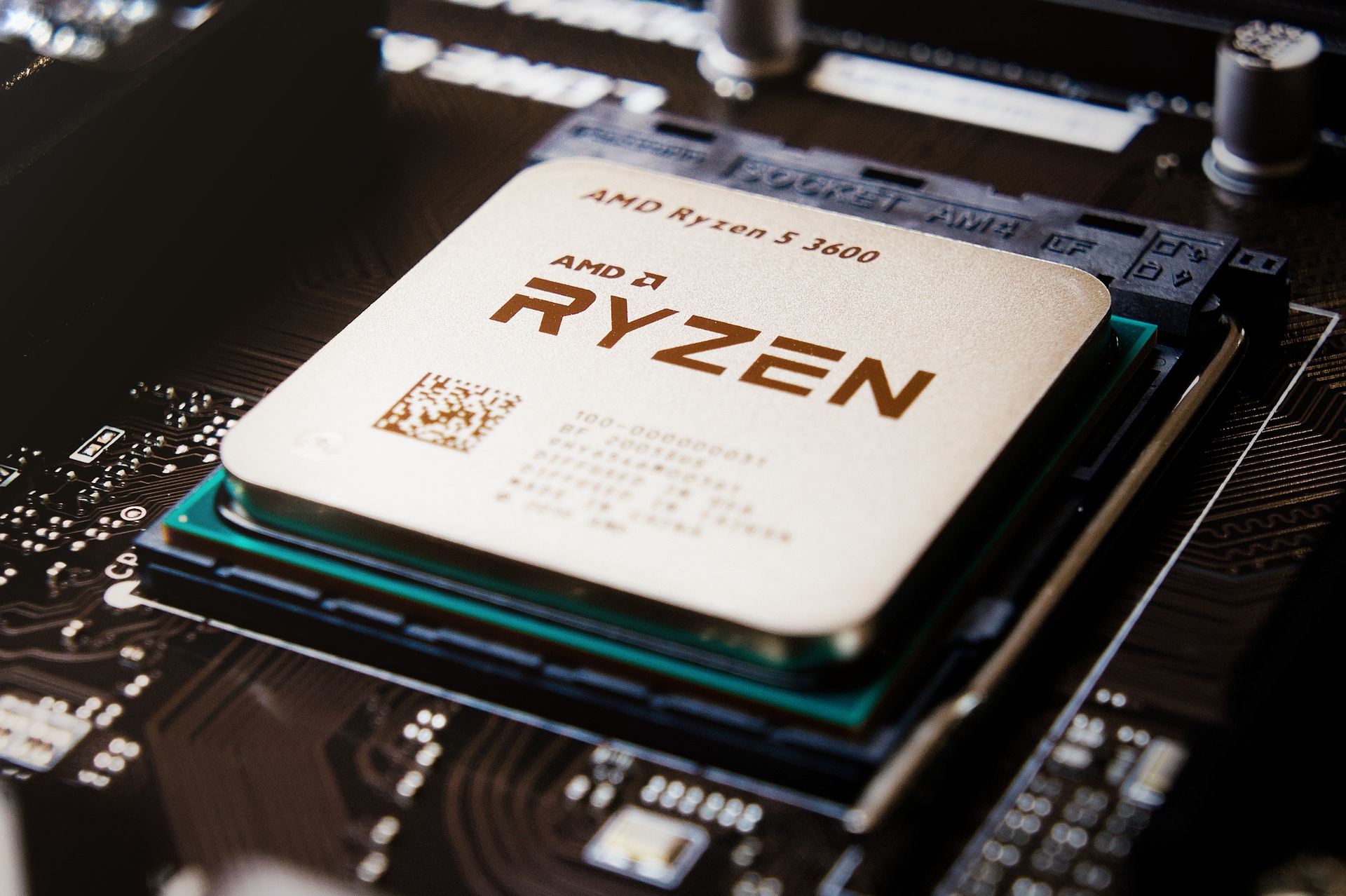

Fortunately, things are somewhat simpler now. There are a range of factors that affect how well a CPU will perform in general usage, but for a long time now, Intel has used the label i3 for its entry level CPUs, i5 for mainstream CPUs and i7 for their premium CPUs (with i9 reserved for its top of the line models). AMD has done something similar with its Ryzen 3, Ryzen 5, Ryzen 7 and Ryzen 9 branded CPUs. On a regular basis (usually annually), the CPU manufacturers release their latest CPUs with that branding to clarify who they expect to buy them. Basic computer for solid performance in everyday tasks? i3 or Ryzen 3. All rounder? i5 or Ryzen 5. Workhorse? i7 or Ryzen 7. You get the idea.

Why do I need to know this again?

Because just knowing whether or not you want i3 or i5 isn’t quite enough. They’ve been using this naming system for a long time now. CPU technology has moved on a long way since Intel first started using the i- prefix. This means that when you’re looking at a CPU, you also need to know when that CPU was released. Why? Well, here’s an example to illustrate:

- The i7-975 was the most powerful, most expensive CPU of its generation, coming in at a launch price of just under $1000.

- The i3-10100F, on the other hand, is the lowest spec, lowest price i-series CPU of its generation, costing under $100 at launch.

Here’s the twist: the i7-975 was launched in 2009 and the i3-10100F was launched in 2020. As a result, the i3-10100F performs roughly 2.5 times faster than the i7-975.

So how do I tell what CPU I need?

The simplest way is to recognise the branding of the CPU and then check to see when that CPU was released (by Googling the CPU model number plus the words “release date”). Because of the speed at which CPU technology increases, a more modern processor is likely to be better performing than a processor from even just a few years ago.

Simplified CPU Branding:

| Usage | Intel branding | AMD branding |

| Basic usage | i3 | Ryzen 3 |

| All round usage | i5 | Ryzen 5 |

| Power User | i7 | Ryzen 7 |

| Top of the line | i9 | Ryzen 9 |

You may also see other branded names. For example, Celeron CPUs are made by Intel but are very weak. They will do for only the lightest computing situations. A Celeron-powered Chromebook is more acceptable than a Celeron-powered Windows machine, which will probably be very slow in everyday usage. In short, I don’t recommend Celeron processors in most usage cases.

A word on Mac CPUs

Up until recently, Apple laptops and desktops used Intel processors. However, in November 2020, Apple released their M1 CPU, which is based on the ARM CPUs that originated in Acorn computers in the 1980s, such as the BBC Micro and the Archimedes. As these CPUs are built in a completely different way to the Intel and AMD processors, nobody knew what to expect from these new Apple CPUs. When they were eventually released, the resulting performance increase was substantial, catapulting Apple computers towards the top of the pile when it came to CPU performance. This has had another notable side effect. Apple laptops have traditionally held a fairly high resale value, but the price of used pre-2020 Apple laptops fell substantially once the M1 models were released.

Why am I hearing about a chip shortage?

The pandemic of 2020 had some catastrophic effects on the CPU market. Factories that produced CPUs lost their supply chain of raw materials and ceased production. All other devices that needed CPUs (including cars, phones, TVs and scores of other devices) were competing for rapidly dwindling stocks of existing CPUs. When the factories eventually began to ramp up production again, the backlog remained from industries all over the world. Short supply but high demand means that even now, CPUs and other computing components are more expensive than they have been for a long time. Hopefully this will subside as we head into 2022.

James

Comments are closed